Pastor Rebecca Ellenson; NBC Mazatlan

Symbols and art have played an important role in shaping the faith of believers, especially before literacy was widespread. They helped a priest to educate, they inspired the mind to things difficult to understand.

Christ was often portrayed as Almighty Lord of All Creation, often in a particular pose called pantocrator—Greek for all powerful. The risen Christ is depicted, crowned, regally overlooking all things, one hand raised in blessing, the other holding the Word of God, the Book of Life.

This mosaic dates back to the late 1200’s and is visible on the upper walls of the Hagia Sofia in Istanbul.

Similar paintings are found throughout the Christian world. This one is in Barcelona.

Today is Christ the King Sunday, the last Sunday in the church year. Next week is the first Sunday in Advent, the season leading up to Christmas. Our texts today are filled with images and symbols of God as ruler over all earth. From Psalm 93 “The Lord is king, robed in majesty, robed and girded with strength.” From Revelation 1: Grace and peace to you from the one who is and who was and who is to come, from Jesus Christ, the ruler of the kings of the earth, to him who loves us and freed us from our sins and made us to be a kingdom, to him be glory and dominion forever and ever. I am the Alpha and the Omega, says the Lord God, who is and who was and who is to come, the Almighty—there’s that word, pantokrator.

This painting hangs in our dining room at home.

When I was about 10 years old, my Dad bought it from the college where he worked. He collaborated with the head of the art department to design the scene. Dad traveled to church youth gatherings and college fairs, recruiting students for Concordia College, a Lutheran liberal arts college in Moorhead, MN. It’s three panels stood, like a booth, behind his recruiting table: all the pursuits of study and life under the dominion of Christ the King, with the words of Colossians 1: 17 across the top: All things hold together in him. The symbol of the trinity behind the figure of Christ in classic pose, the book of life in one hand and the orb of the world in his upheld right hand.

What I like about this painting is that it is full of real life—sports, children, art, work. It’s relatable all things hold together; Christ is in the midst of real life. I’m sure I have been shaped by looking at it, day after day from the dining room table. Christ holds the world and all things. Christ, crown on his head, is king.

Christ the King Sunday is a very new addition to the liturgical calendar. It was instituted by Pope Pius 11th in 1925 as a countercultural observance. He saw a world becoming ever more dominated by totalitarian governments and exploiting economies and knew that Christians, all types of Christians, needed a reminder of where our allegiance and trust must be. Thus, Christ the King Sunday. This is not a Sunday celebrating that Jesus is the King of our hearts or our souls or our spirits. This is a Sunday celebrating that the Crucified and Risen Christ is the King of the Cosmos, of all things.

The early followers of Jesus greeted one another by saying Jesus is Lord. That may sound super spiritual to us, but in their day that greeting was radical and dangerous. Citizens of the Roman empire said “Caesar is Lord,” the way citizens of the Third Reich said, “Heil Hitler.” But Christians insisted, that “Jesus is Lord. Hail Jesus.” That is what got them burned at the stake and fed to lions. They were martyred because they refused to bow down to the political system.

When we say that Jesus is Lord or that Christ is King or that Jesus Christ reigns or we talk about the Kingdom of God, we are talking about something real, tangible, everyday, actual. Jesus is Lord and money is not. Jesus is Lord and political parties are not. Jesus is Lord and fame is not. Jesus is Lord and The United States, or Mexico, or Canada is not. Jesus is Lord and violence is not. Jesus is Lord and religion is not. Jesus is Lord and as followers of Jesus we give our allegiance to him, place our trust and faith in him. Christ Jesus reigns as lord and king over all.

Ok, back to the images of Christ as King. In our gospel reading today, Jesus hangs between heaven and earth, between the power of God and the powers that be. “Are you the King of the Jews?” Pilate asks. “Do you ask this on your own, or did others tell you about me?” he puts back to Pilate. Everything in the conversation—indeed, everything in the Gospel—has been pointing toward verse 36. “My kingdom is not from this world,” says Jesus. If it were, his followers would take the usual steps by the usual means to rescue their king. This all leads up to his hanging literally, on the cross, with the sign “King of the Jews” over his head.

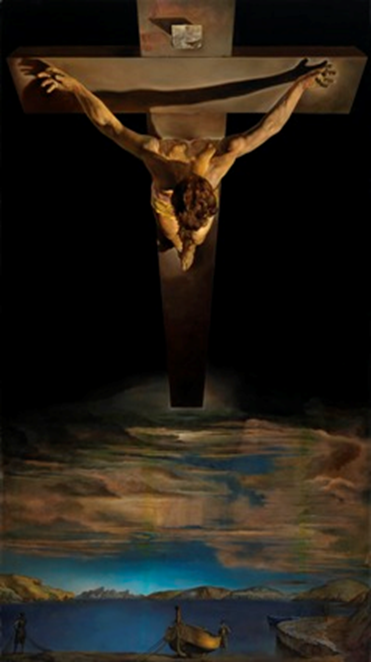

Those pieces of art I showed you before don’t really capture the whole truth about Christ. Surrealist painter Salvador Dalí, painted a work called Christ of Saint John of the Cross. On the bottom of his sketches in preparation for the painting Dali wrote about a dream he had experienced, what he called a “cosmic dream,” in which he saw an image in color that he said represented the nucleus of the atom which took on a metaphysical sense. “I considered in ‘the very unity of the universe’ the Christ!” As he was preparing to paint his dream someone showed him a sketch by the 16th century Spanish mystic, St. John of the Cross who is remembered for his reflections on the dark night of the soul.

The composition of Dail’s work was based on the sketch. He wrote: I worked out geometrically a triangle and a circle, which aesthetically summarized all my previous experiments, and I inscribed my Christ in this triangle.

Here it is.

I love the sharp darkness cast by Christ’s outstretched arm. Christ crucified contemplates an abyss skeined over with clouds before (or maybe after) a storm. There is something antigravitational about the perspective, how Christ hangs from the cross and the cross hangs in the sky so very un-wood-beam-like.

For me, this painting conveys something of the sacrificial regency of Christ, the King who came not to be served but to serve, the one who “did not regard equality with God as something to be grasped” (Philippians 2:6).

Christ’s power and glory comes by way of the cross. The polarities of his kingship are reversed. And we, the people drawn to him by his lifting up on the cross, have become a kingdom, “priests serving his God and Father,” says Revelation, whose vision of power is reversed as well. The cross of Christ calls power into question but also serves as the basis for a different sort of power. The genius of the gospel hangs together on the cross: the cross with its power that is not power, the cross that takes shape as the pattern of our lives, the foundation of Christian thought that is always also a kind of anti-foundation, the disturber of worlds.

In our gospel today, John 18, Jesus, the king who is crucified, calls into question the assumptions of power. We’re left asking: Who stands before whom? Who interrogates whom? Who is the king? Not the one who commands iron legions but the one who willingly lays down his life for the sheep. “Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice,” says Jesus, speaking of his kingship and more. But brutality and blood have crumpled Pilate’s sense of truth down into irony. “What is truth?” he asks.

For Christians, this means that any exercise of power that does not trace back to the self-sacrificial love of the cross is illegitimate, having lost its proper grounding in the cruciform mandate of God. I say that at the risk of sounding too academic. But that’s really the heart of the Christian faith, isn’t it? It’s how we live day to day, how we want and how we purpose, how we steward influence, money, position, and all the rest toward God’s ends on behalf of the least of these. The cross shapes the power we use to work with and under and no longer over, at least not over in the same way.

Jesus’ cruciform kingdom is the basis for a different sort of power. Jesus has trampled down Death by death, and now it’s in that power of his name that the church preaches and heals and teaches and draws together the broken.

This is not a metaphor. This is real power of a different order that rescues us from the bondage of sin, from the fear of death, from slavery to our own little selves. All power resolves into Jesus, is follows his pattern: resurrection. “To him be glory and dominion, forever and ever.”

It is hard to hold onto that vision or version of power. It’s so easy to be pulled into the crowd, crowing for Barabbas in whatever new form that base but reliable power might take in our time, whetted sharp and holstered up. Whenever the church, throughout the world, throughout time, has leaned on Barabbas-power it has stumbled. Whenever the church plays the long game of faithful dependence on the Lamb that was slain, it ultimately wins. Parades of nuclear-tipped military power snaking through concrete capitals impress, but the cross in its turnabout mystery wins in the end.

Christ, crucified, is the one in whom all things hold together, the one who we need to know if we’re going to know anything else. Amen.